Where in the galaxy will we mine lithium?

Interplanetary resource wars are nothing new in science fiction, but recently, a few popular shows have converged on one resource in particular: lithium.

In the second season of For All Mankind, an alt-history show about the Cold War space race, the U.S. and the Soviet Union are fighting for control of a lunar lithium deposit that both superpowers wish to mine, presumably to build new batteries for their lunar rovers. Lithium fuels the fusion reactors that power spacecraft in The Expanse, and it plays a starring role in Season 4 of the show, which takes place on a Belter-run lithium mining colony. Then there’s Star Trek’s famed “dilithium,” a fictional substance that shapes the entire universe by enabling faster-than-light warp drive to work (er, somehow). In Season 3 of Star Trek: Discovery, which aired last fall, we got our first taste of what life might look like in a version of the Federation where this lithium-inspired wonder material no longer exists.

As someone who spends a significant amount of time writing about the importance of lithium on 21st century Earth, I’m not surprised to see the element coming into focus in science fiction. Lithium underpins the batteries that power everything from cell phones to electric cars, and unless we find new sources soon, the world could face a lithium shortage in the near future. That could fuel the same sorts of conflicts we see play out on a cosmic stage in shows like For All Mankind and The Expanse. Still, pop culture’s increased interest in the humble three-proton element made me wonder: Assuming that future humans still need lithium to charge their iPhone 57s and power their fusion drives, where exactly will they mine it?

A lightweight element that dissolves in water readily, the highest concentrations of lithium on Earth are found in salt flat brines that formed following the evaporation of ancient lakes, and in pegmatites, igneous rocks that form from extremely water-rich magmas. It stands to reason that if we want to find lithium ores elsewhere in the Solar System, we should be looking for celestial bodies where similar types of rocks and minerals formed due to similar geologic processes.

Unfortunately, that pretty much rules out the Moon.

University of Florida planetary scientist Steve Elardo told The Science of Fiction that while Earth and the Moon have similar bulk concentrations of lithium in their crusts and mantles — about 1-2 parts per million — the processes that concentrate lithium to thousands of parts per million in ores on Earth, including the formation of lithium brines following the evaporation of a water body, “don’t happen on the Moon.” Most of the Moon’s ancient crust, Elardo says, formed from a lunar magma ocean shortly after the giant impact that created Earth’s satellite. The dark patches that cover parts of the Moon’s surface, meanwhile, are basaltic lava plains from eruptions that petered out about a billion years ago.

“Neither processes really concentrated [lithium] to abundances more than a few 10s of parts per million, which I very highly doubt would ever be economically viable” to mine, Elardo wrote in an email.

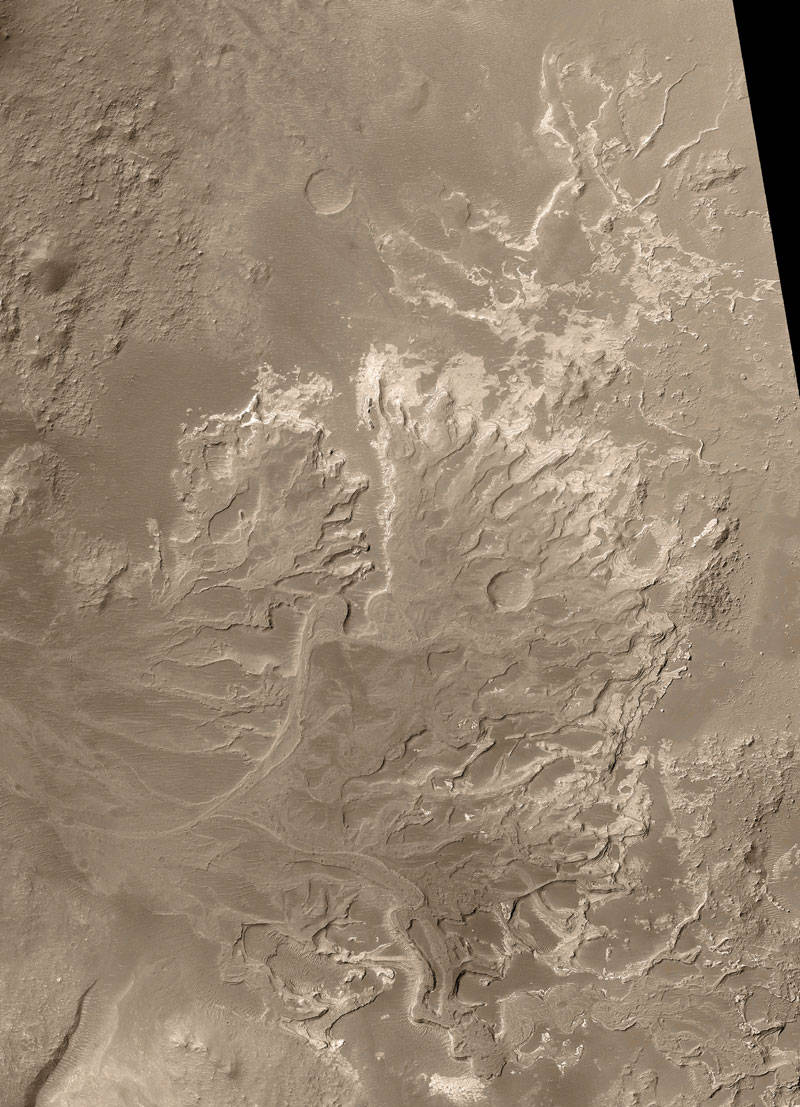

Elardo suspects Mars would be a better bet, given the extensive evidence that its surface was shaped by flowing liquid water in the distant past. “I don’t think Mars had many, if any, pegmatite magmas,” he said, “but there is plenty of evidence for past brines and evaporite mineral deposits on Mars.” Washington University in St. Louis planetary scientist Bill McKinnon agrees that Mars is a more promising lithium hotspot than the Moon given its watery history, adding that without plate tectonic activity, the production of rocks like pegmatite “was probably limited.”

More lithium might be found in the icy outer Solar System, where there’s plenty of water available to pull the metal out of rocks. Lithium could be present in low concentrations in the oceans beneath the icy surfaces of Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's Enceladus, just as it can be found in seawater on Earth. And Enceladus's seawater is conveniently spewing out of geysers at the moon’s south pole. But we don’t yet have a method for extracting dilute lithium from Earth’s oceans, and Enceladus’s alien seas could prove an even bigger challenge.

“In general, we think that Enceladus ocean water is about 5 times less salty than Earth seawater, so I would expect lithium to be in the Enceladus ocean but at a more dilute level than in seawater,” planetary geochemist Christopher Glein of the Southwest Research Institute wrote in an email.

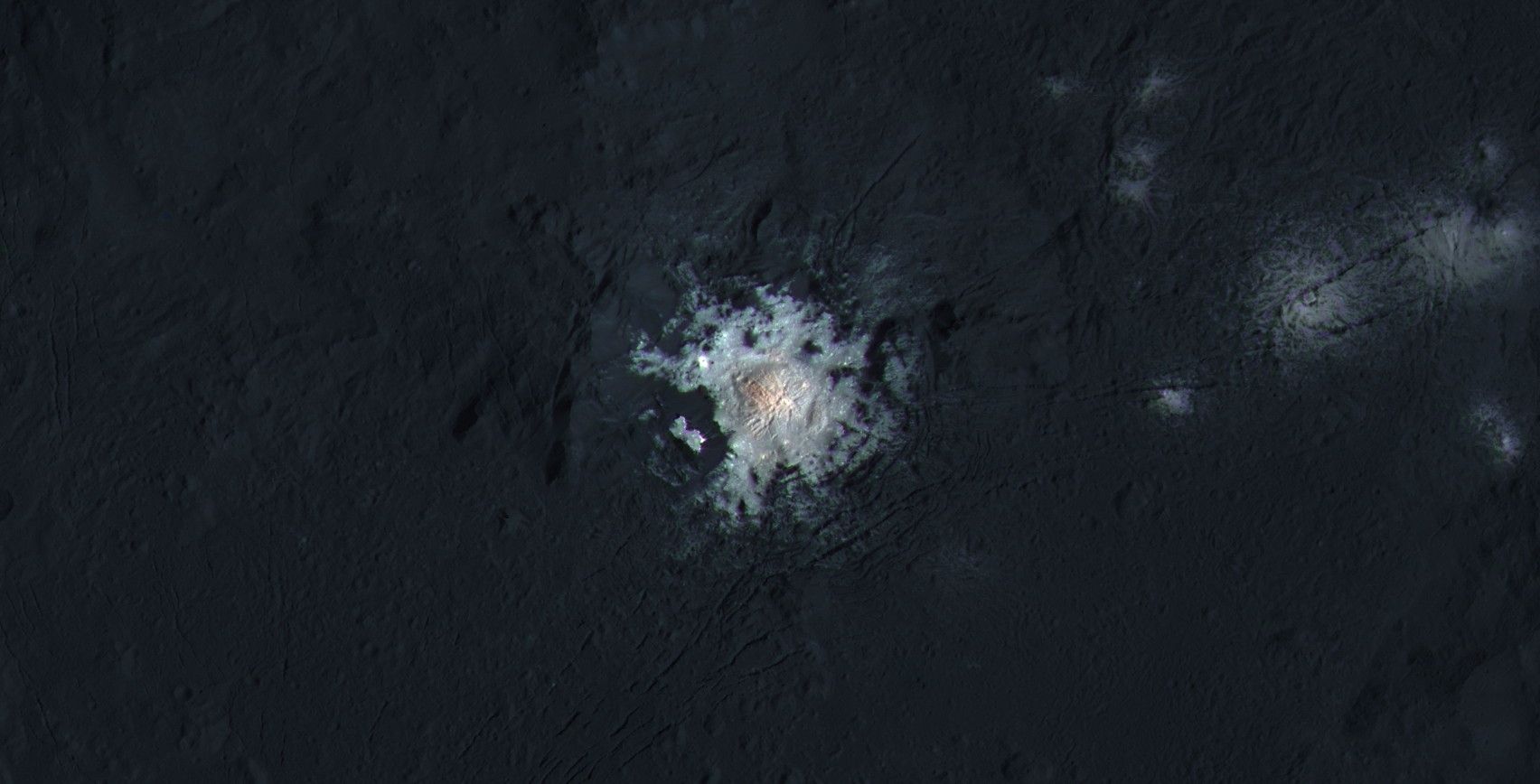

McKinnon suspects that the best place to find economically viable lithium deposits beyond Earth would be an asteroid whose surface has been altered by water in the past, but where most of the water has long since evaporated. Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt, seems like the ideal place to begin the search. When NASA’s Dawn spacecraft visited the dwarf planet in 2015, it discovered gleaming bright spots all over the surface. Scientists eventually determined that these are enormous deposits of salt, mixed with a bit of water ice. A collection of studies published last year concluded that the bright spots hail from an extensive subsurface brine layer that gets partially excavated during impacts.

McKinnon emphasized that there’s “no evidence” for any lithium deposits in the bright spots of Ceres. “But it stands to reason that the lithium that’s in the rocks that are in Ceres has been leached by water and concentrated upwards” he said. So, while Mars has already strip-mined all of Ceres’ ice in The Expanse, maybe there’s some lithium kicking around that the Red Planet’s mining corporations missed.

If we were able to travel beyond our Solar System — an unlikely prospect without physics-defying warp drives or at least robust generation ships — perhaps we could find a star system that won the lithium lottery. Today, most of the lithium in our galaxy is produced during classical novae, stellar explosions that occur when gas from a larger star falls onto a compact stellar remnant called a white dwarf. Astrophysicist Sumner Starrfield of Arizona State University says there are about 50 of these lithium-producing explosions popping off across the galaxy each year, and that they are “pretty well distributed” throughout the Milky Way.

Unfortunately, that means there are probably no galactic hotspots of lithium. In other words, if we do discover any wormholes or alien ring gates networks out there, we’re just going to have to hope they lead somewhere interesting.

Top image: An astronaut rappels into a lunar crater in "For All Mankind". In the show, humans have set up a permanent lunar base near a mineable deposit of lithium. Credit: Apple TV+